Mirror, Mirror

2025

Mirror, Mirror was written my final semester of undergrad in my capstone art history class. The essay explores themes of gender, race, and sexuality within the works of Claude Cahun, Cindy Sherman, and Carrie Mae Weems. More specifically, Mirror, Mirror explores how these artists use photographic self-portraiture to form and question identity. Another important aspect of the works discussed in this essay is the use of a mirror to draw attention to the act of seeing and being seen.

From grade school drawings in crayon to ancient works in museums, nearly everyone has interacted with a portrait. Portraiture can tell viewers about the artist's and subjects' values, status, and ideology. Too often, portraits can be taken as objective representations of reality rather than a constructed image. Portraits are not only a means of representation, but a way for artists to make claims about their values and motivations. This is especially true of self-portraits because they tell viewers how the artists see themselves, and in turn, how they want to be seen. Artists Claude Cahun, Cindy Sherman, and Carrie Mae Weems have all used self-portraits to question the performative nature of gender and its intersection with marginalized identities. Whether they are exploring gender, gender-nonconformity, or race, all three artists assert their autonomy by placing themselves both as the photographer and subject in their photographic self-portraits. Though Cahun, Sherman, and Weems’s work is visually distinct, there is a common motif throughout much of their work: the mirror. Most people first become acquainted with their image through their reflection in the mirror. To look at oneself in the mirror is often the only time people experience themselves both as subject and spectator. These three artists embrace the pleasure and opportunity presented through self-spectatorship to understand and construct identity. Through their photographic self-portraits, Claude Cahun, Cindy Sherman, and Carrie Mae Weems explore the performative nature of subjectivity and the complexities that arise with questions of gender, gender-nonconformity, and race. Though these artists’ careers span the 20th century, they all use mirrors in their work to explore self-spectatorship and the frame as a way to define how identity can be formed.

The use of the mirror is a long-held tradition in Western self-portraiture. The presence of the mirror allows artists to underscore the act of looking and, in turn, their perception of self. Another common motif seen in many self-portraits is a visual representation of the act of art making. The inclusion of artistic tools, such as a paintbrush or camera, signals to the viewer that they are looking at an artist. Gabriella Giannchi, author of Technologies of the Self-Portrait says that the self-portrait is “a crucial indicator of what artists understand not only by a ‘person’ but also by a ‘self’, a rendering of themselves as a subject, often seen in the act of painting, and a staged (social, professional, political, medical, etc.) object, a presence to be looked at, or even interacted with, by others” (13). By doing this, the artist indicates the act of making through the performative inclusion of their tools. While Cahun, Sherman, and Weems do not explicitly show their tools, they use the mirror as a stand-in for the camera. All three artists also heavily feature frames within their work which act as a substitute for the frame of the camera. Additionally, the use of the mirror brings to mind the mechanics inside a film camera.

In addition to the technical and compositional uses, each artist uses the mirror as a tool to understand themselves and their gender and racial identity. This is especially notable for these artists as members of marginalized groups whose depictions in art history have either been non-existent or one-dimensional. By centering self-spectatorship, Cuhan, Sherman, and Weems demonstrate how they actively control and reclaim how they are seen. They frame both the act of looking and the performance of being seen not only as important for their understanding of self, but as a way to define how they are seen by the viewer.

Claude Cahun was a gender-nonconforming photographer who began their career in France as the Surrealist movement began to form in the 1920s. While it is difficult to concisely define a movement that spanned numerous media and included countless artists, at its core, Surrealism aimed to explore the unconscious. Artists often did this by creating dream-like work that asked the viewer to question what they were looking at. Another thematic throughline in much Surrealist work is an attempt to access the sexual subconscious. From the inception of the Surrealist movement, photography, collage, and analog editing techniques were always present. While photography was not a particularly new medium in the 1920s, artists were experimenting with new ways of exploring the subconscious through the perceived objectivity of photography to create works that make the familiar seem strange.

While it is true that many female artists were working within Surrealism, representations of women in Surrealist works were often one-dimensional. There are countless examples of male artists using the female form to project meanings about the subconscious. Fionna Barber explains that for a male Surrealist, “the object to which his desire would be drawn was the mysterious female, whose image becomes saturated with meaning. The female body as signifier of male desire thus becomes the catalyst for the poet's or artist's access to the unconscious” (438). In many of these works, women are not seen as individuals but rather as vessels onto which male artists could project meaning or desire. This is what made it so notable when non-male artists began to challenge the norms of representation.

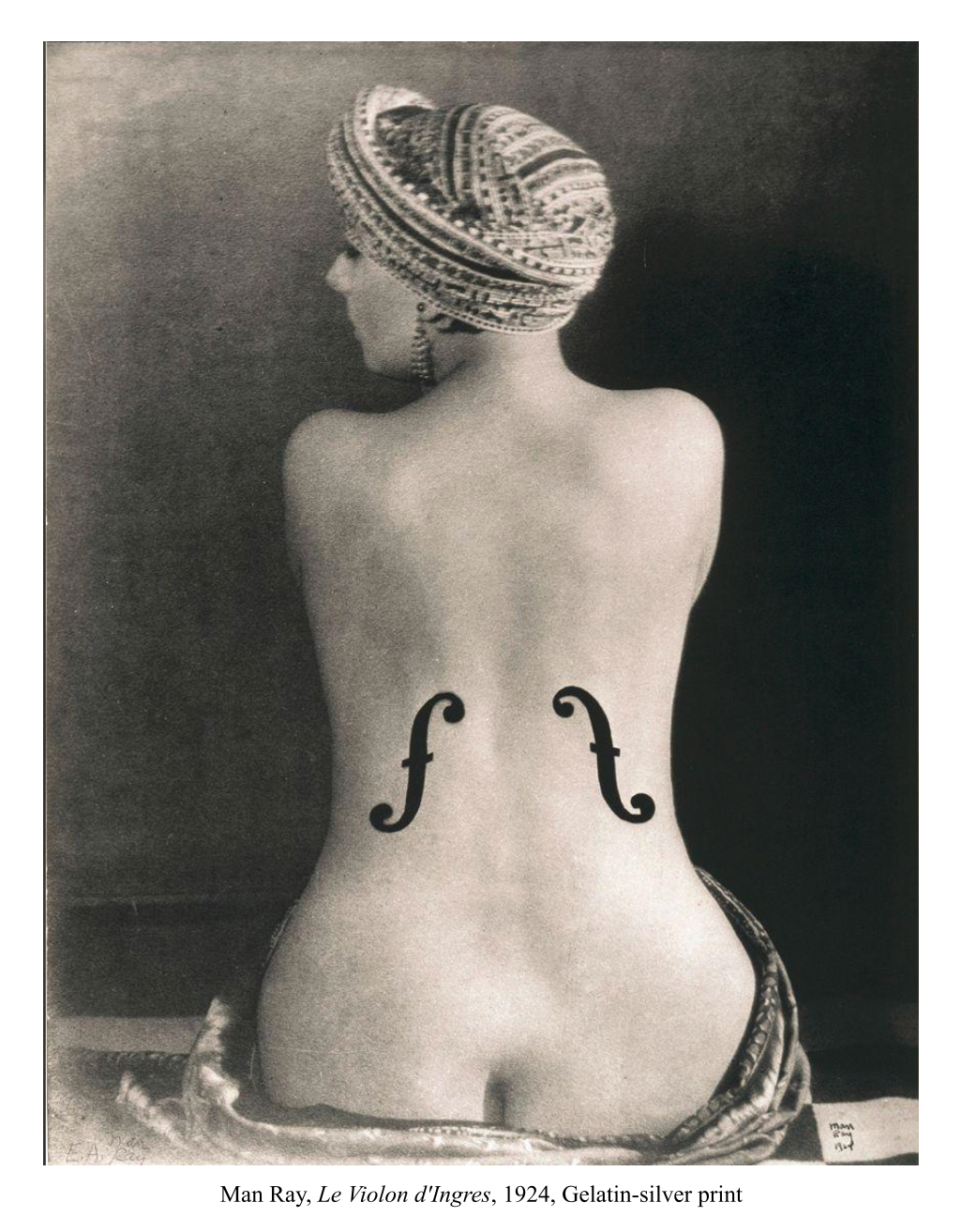

Though women have long been objectified throughout art history, photography allowed artists to manipulate the image in ways not possible with other media. Because Surrealism largely aimed to uncover the sexual unconscious, many male artists photographed women in hypersexual ways. These male artists played with fragmented or collaged images of women to express desires and attempt to make the subconscious visible. French photographer Man Ray made many images of women, but none take the objectification of the female subject as literally as his 1924 Le Violon d'Ingres. Inspired by the work of French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Man Ray took a series of nude photographs of model Kiki de Montparnasse wearing only a turban. In this photograph, de Montparnasse is seated with her back to the camera and her arms in front of her so they are not visible to the viewer. Man Ray took the original image, painted f-holes — as you would see on a stringed instrument — and rescanned the photograph. By doing this, de Montparnasse’s body is turned into a musical instrument, a literal transformation of the female body into an object.

This objectification of the female form is something film scholar Laura Mulvey discusses in her seminal text “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” The depersonalization of subjects through abstraction takes many forms, but ultimately is used to turn women into narrative objects or objects of desire. Mulvey explains some of these strategies, saying, “For a moment the sexual impact of the performing woman takes the film into a no-man's-land outside its own time and space... Similarly, conventional close-ups of legs or a face integrate into the narrative a different mode of eroticism” (716). Though Mulvey is discussing film in this particular passage, these techniques’ roots lie in photographic conventions. Photographers like Man Ray used fragmented female forms as props within their work. These conventions carried on throughout the rest of the 20th century and through to the present. It is because of these norms set in place by early photographers (and previously male artists working in other mediums) that female and gender-nonconforming artists needed to develop their own visual language as a means of representation.

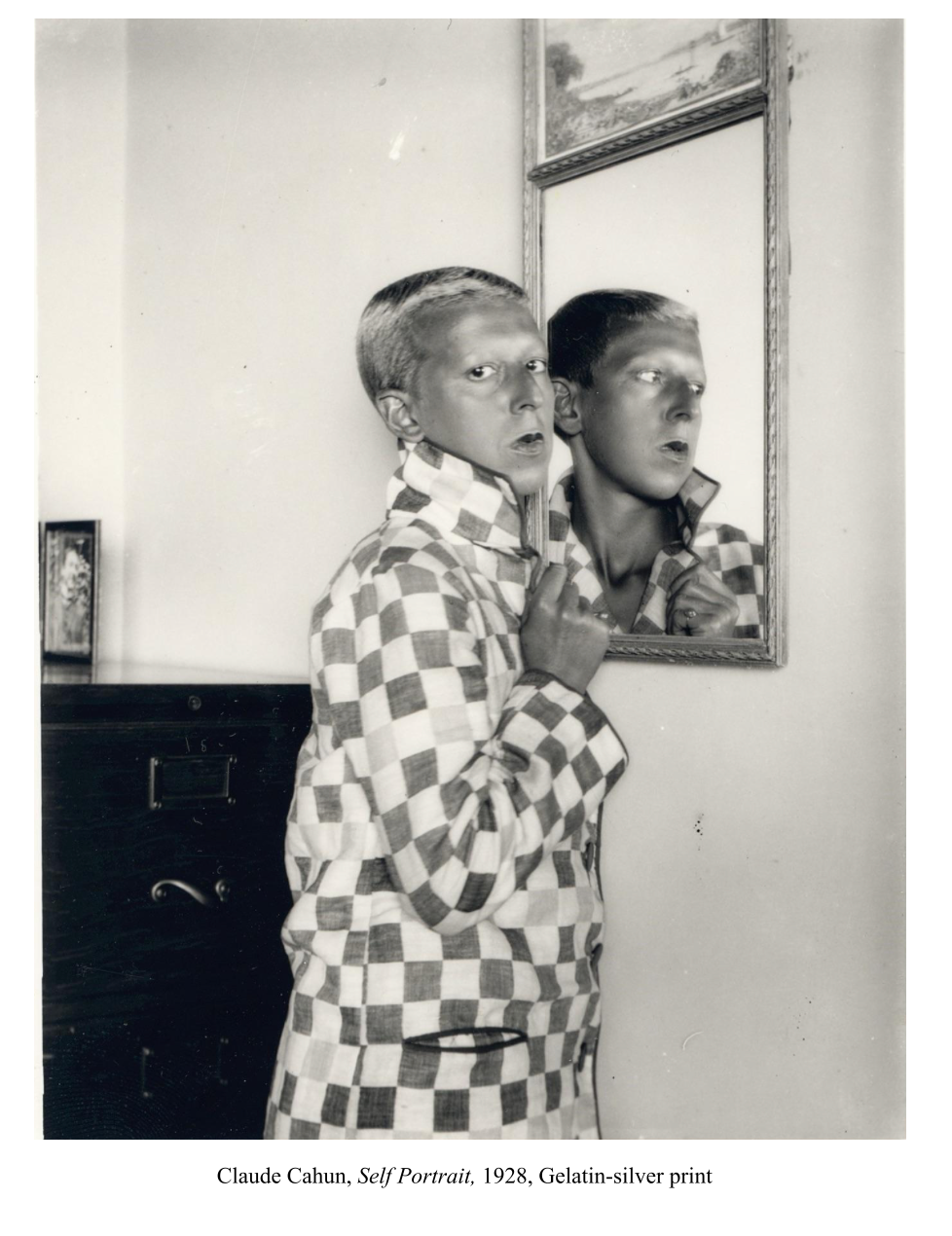

While Claude Cahun's work was largely unrecognized at the time, contemporary conversations about Surrealism, particularly Surrealist photography, have begun to increasingly center their work. The majority of their work consists of self-portraits in which they often alter their appearance through costuming. These works are not candid portraits, but rather staged performances that center on the performative nature of gender. One of Cahun’s most famous and arguably most interesting pieces is their 1928 Gelatin-silver print photograph, Self Portrait. This photograph is deceptively simple at first glance. It consists of a three-quarter portrait of Cahun looking over their shoulder at the viewer. They are wearing a men’s checkered jacket with the collar popped and a short buzzed haircut. Cahun’s styling walks the line between androgyny and masculinity. Their setting is ambiguous and gives the viewer little information. The only discernible object in the photograph is a small wall mirror that Cahun is standing in front of, but importantly, not looking at. Their gaze is pointed at the viewer rather than at themself, leaving their side profile on full display. Rosalind Krauss explains this saying: “Cahun’s autobiographical project not only puts [them] on both sides of the camera —simultaneously the subject and object of representation—but it also endows [them] with the power of both projecting the gaze and returning it, as Claude’s eyes meet ours” (27). Cahun’s unbroken eye contact signals to viewers their control not only over the portrait but over themself. While previously eye contact from a feminine subject would be seen as suggestive, Cahun’s eye contact not only flips gender expectations, it also establishes them as an autonomous figure. The control that is communicated through their gaze is only emphasized when one remembers that this photograph is a staged self-portrait. By returning the gaze, Cahun acknowledges the power of being both subject and photographer.

In addition to their gaze, Cahun also gives the viewer multiple versions of themself within a single photograph through their use of a mirror. A small household mirror like the one seen in this work is something that nearly everyone owns. It is people’s primary, if not only, way of observing and perceiving themself. While it might seem mundane, the act of viewing oneself shapes the way people come to understand themselves. Notably, Cahun is not interacting with their reflection. Rather, they look directly into the camera, refusing to break eye contact. Their body language is stiff and not traditionally feminine. It seems as if the photographer has caught Cahun off guard. This, of course, is only a momentary illusion, broken after the viewer remembers the staging necessary for taking a self-portrait of this nature. By doing this, Cahun simultaneously centers the pleasure of self-spectatorship, yet, notably, denies it, thus highlighting the complex relationship between subjectivity and gender-nonconformity.

This is compounded by their reflection in the mirror. The viewer sees Cahun not only in the flesh but viewing their reflection as well which creates an odd disconnect and gives the photograph an uncanny quality. Because viewing oneself is an intimate act, seeing Cahun’s reflection feels almost voyeuristic. Katy Kline points to the oddity present in viewing Cahun’s reflection in her essay “In or Out of the Picture.'' She explains, “The ‘real’ figure registers the presence of the viewer and does not flinch from eye contact. [their]other half, the mirror image, however, averts [their] eyes gazing into the unknown. The brittle gleam of the glass refracted into the faces cranks up the emotional pitch. The two faces register a shock; they have been interrupted by some intrusion from the outside world in the midst of a private exchange” (69). Through their use of a mirror, Cahun is creating two subjects for the viewer to consider, one that meets their eye and refuses to break away, and a second stuck within the confines of the mirror’s frame. By doing this, Cahun demonstrates their role both as subject and photographer, underscoring their autonomy in creating this work and in turn, defining their identity.

The presence of multiple iterations of the artist plays two important functions when thinking about Cahun's work within a larger conversation between Surrealism and the psychoanalysis that was so popular at the time. The first is a representation of multiple gendered figures within the frame, which is underlined by the use of a mirror. By photographing their reflection, Cahun centers the act of looking at, and in turn, questioning oneself. The second function of the mirror is likely not as legible to contemporary viewers. It is hard to overstate the importance of psychoanalysis to the Surrealist movement. Surrealist artists were interested in exploring the unconscious, a theory popularized by the Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud. By showing themselves on either side of the mirror, Cahun creates multiple versions of themself, and in turn, borrows the visual language and ideas of the time. They reference both their conscious and unconscious self. While this would be common at the time, it is notable because they are a non-male artist representing themself not as a vessel for the subconscious but rather as an active multi-dimensional subject.

Another artist whose work explores similar themes of gender performance in her self-portraits is Cindy Sherman. While performativity is at the center of both Cahun and Sherman’s self-portraits, these two artists explore gender, subjectivity, and what it means to occupy both sides of the camera in different ways. Sherman’s best-known series, Untitled Film Stills, was created between 1977 and 1980. In these works, she explores female stereotypes and archetypes constructed through popular culture. Each of the over 50 photographs in the series feels as if it is a still taken from a classic film. In each photograph, Sherman styles herself into a variety of characters and strikes poses to create manufactured vignettes. Even though Sherman embodies the same “characters” in a handful of the Untitled Film Stills, there is no overarching narrative, nor are there direct references within these photographs. Rather, Sherman is utilizing the existing visual language of media to construct these alter egos. Sherman’s work asks viewers to question what it means to look at a reference with no original subject. These photographs exist in a space that feels eerily familiar yet cannot be traced back to anything in particular. While Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills do not borrow the visual language of Surrealist photography, she does incorporate elements of the uncanny. By creating a false reference, Sherman points to how gender stereotypes are constructed and, in turn, how they influence one's sense of self.

Film scholar Mary Ann Doane explains femininity as performance, saying that “Womanliness is a mask which can be worn or removed. The masquerade's resistance to patriarchal positioning would therefore lie in its denial of the production of femininity as closeness, as presence-to-itself, as, precisely, ‘imagistic’” (81). Sherman embodies this idea of the masquerade in all of her Untitled Film Stills. While not all her characters are hyper-feminine like Doane suggests, Sherman expands this idea of the masquerade through physical transformations. By transforming herself into dozens of female characters, Sherman underscores the ubiquity of one-dimensional depictions of women. Her use of the mainstream cinema visual language allows viewers to recognize these snapshots instantly. By doing this, Sherman asks viewers to question depictions of women in the media and, in turn, how their own definitions of womanhood and femininity are constructed.

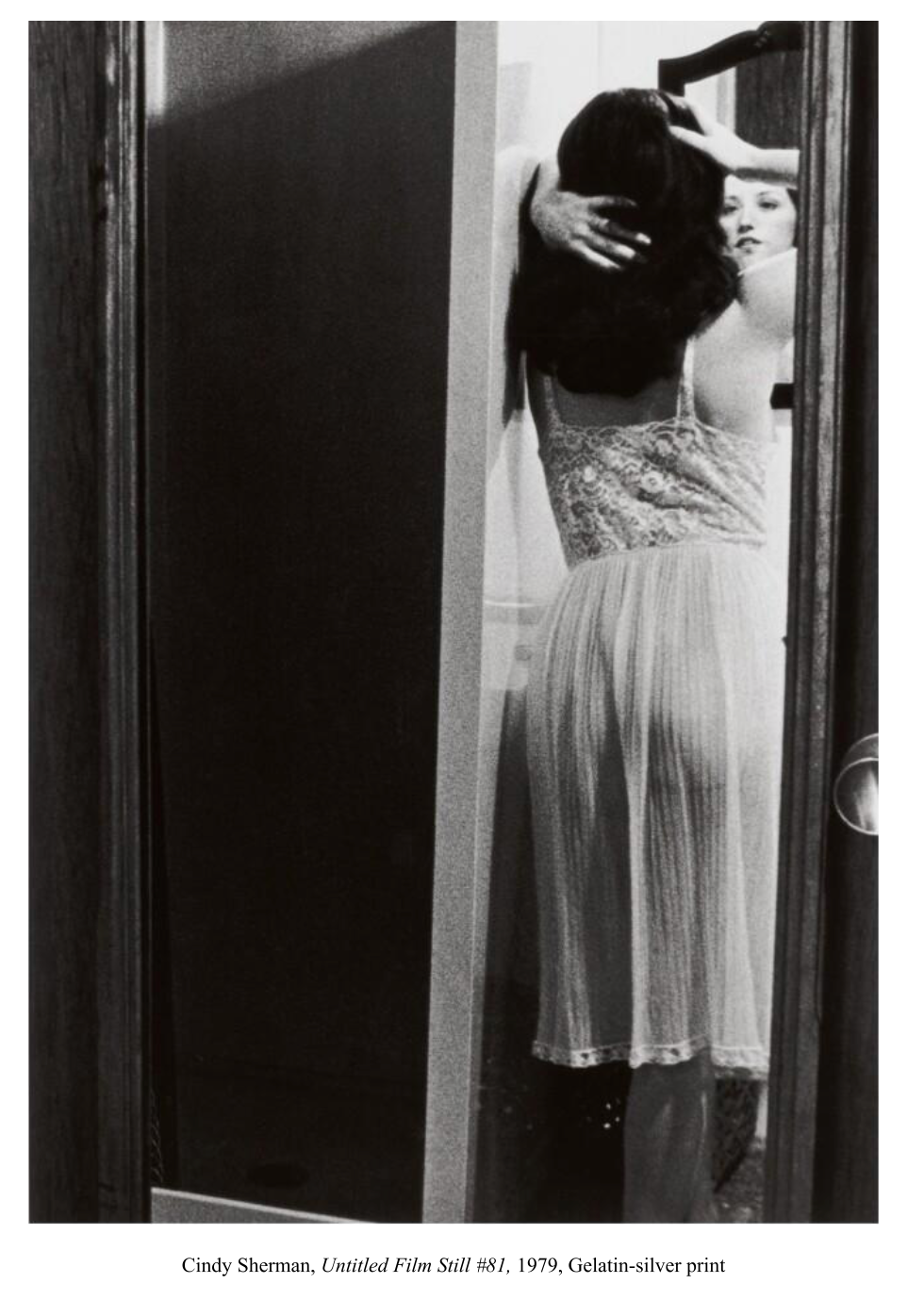

Much like in Cahun’s 1928 Self Portrait, Sherman utilizes a household mirror to explore both self-representation and self-spectatorship in many of the Untitled Film Stills. Her 1979 photograph Untitled Film Still #81 parallels Cahun’s Self Portrait’s acknowledgment of the viewer. In this photograph, Sherman stands admiring her reflection in a bathroom mirror while fixing her hair and wearing a sheer nightgown. Her stance is confident and even slightly suggestive. The character that Sherman creates in Untitled Film Still #81 feels self-assured within this domestic space and with the act of self-spectatorship. It feels as though the viewer is gaining an intimate look at a private moment due to the framing of the photograph. The camera is placed outside the bathroom and looks at Sherman through the cracked door.

Despite the placement of the camera, this photograph does not feel voyeuristic like one might assume. According to Krauss, “The continuity established by the focal length of the lens creates an unimpeachable sense that her look at herself in the mirror reaches past her reflection to include the viewer as well” (122). Though this is very different from the feeling given in Cahun’s acknowledgment of the viewer, both photographs ask the viewer to consider the artist's subjectivity. Both artists simultaneously acknowledge and break through the barriers of the frame by returning the viewer’s gaze. Though both artists break the illusion of the photograph by looking back, importantly, they remind the viewer that they are looking at a constructed photograph through their use of the frame. Whether it is the door or the mirror’s frame itself, Sherman and Cahun both acknowledge the inherently constructed nature of a photograph while breaking the barrier between subject and viewer.

There is also something very interesting happening with Sherman and Cahun’s gaze in both of these portraits. Cahun’s eyes meet the viewer, but feel almost defensive, as if we caught them in the act of looking at themselves performing gender-nonconformity. Compare this to Sherman, who not only looks at herself in the mirror but uses it as an opportunity to practice the performance of femininity and desirability. This open acknowledgment of the performative nature of gender is key to the conceptual backing of Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills. Sherman explores what it means to present oneself as a stereotype and a copy with no original. Sherman does not lean into femininity to celebrate or embrace the one-dimensional depiction of women but rather to draw our attention to this pattern.

While Sherman’s work explores the way that depictions of women influence the way women learn to see themselves and learn to perform femininity, it is important to note that being seen in the media is inherently a privilege. Many scholars and artists of color have explored the nature of non-white-subjectivity in the years following Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills. For over four decades, Carrie Mae Weems has been making work that merges personal experience with systemic issues of race, class, gender, and identity. Particularly, she is interested in Black-subjectivity within photography. Emmanuel Jones describes her work by saying, “Weems employs black subjectivity and black female subjectivity with incredible skill and to radical effect, actively disrupting the White cultural hegemony by portraying Black people not in relation to another race or as tropes, rather elevating them to the positions of White figures” (Jones). By doing this, Weems is using a visual language that has been used throughout art history. As a result, viewers from across different backgrounds can read these images because of this language that has been established over centuries, mostly by white European men. Rather than swapping subjects, Weems uses this visual language to explore issues and interests that affect her on a personal level and systemic and structural issues she has experienced as a Black woman.

Photography as a medium and Black-subjectivity have an extremely complex history. Louisa Potthast explains that “photography plays a crucial role in the construction of stereotypes – invented by white men in the middle of the nineteenth century, photography from the early days was utilized to create the image of ‘the Other’…Photography served to allegedly prove racial inferiorities in the emerging pseudo-sciences of the nineteenth century” (3). While photography has been used in harmful ways since its invention, it has also been utilized by those in marginalized groups to reclaim the ability to self-represent. Unlike a painted portrait, photography became fairly affordable by the mid-to-late 19th century. It allowed subjects to commission and create portraits of themselves more democratically and immediately than was possible with other media. Notably, Frederick Douglass was a proponent and early adopter of photography as he felt that it allowed him to project the power and social standing that had long been associated with portraiture. In fact, Douglass was the most photographed person of the 19th century (National Parks Service). Earlier adopters of photography were interested in the perceived “naturalness” of the medium. While it is true that the camera captures what is in front of it, the fact that a photograph must be taken and staged by a photographer means it can never be truly neutral. Though there are notable instances of Black-subjectivity in photography as early as the 19th century, Overall, Black subjects, particularly Black women, have been underrepresented within photographic and film history. When Black women were shown in photography and film, they were depicted in one-dimensional ways. Potthast explains this saying, “Black women have been assigned three main stereotypes: The mammy, the jezebel, and the sapphire” (3). In her work, Weems is interested in challenging these stereotypes by creating complex work that centers around Black female subjects.

Because of this lack of representation of multi-dimensional depictions of Black women, Black female spectators have been left with no one to identify with in most mainstream media. In her essay “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” bell hooks defines a type of looking in which Black spectators, particularly women, can resist patriarchy and white supremacy through a critical lens when watching mainstream media. She calls this lens the oppositional gaze (116). This is not only true of cinema and television, it extends to photography as well. hooks goes on to elaborate on her thesis, specifically pointing to the unique challenges faced by Black female spectators, saying, “Black female spectators have had to develop looking relations within a cinematic context that constructs our presence as absence, that denies the ‘body’ of the black female so as to perpetuate white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be looked at and desired is ‘white’” (118). Where Sherman questions what it is like to construct one's self-image from the media, Weems and hooks question what it is like to attempt to construct an identity out of absence.

Weems and hooks had a working relationship that influenced both of their practices. A transcript of one of their conversations can be found in bell hooks’s Art on My Mind: Visual Politics:

CMW: After thinking about postmodernism and all this stuff about fractured selves, and so on, when I was constructing the Kitchen Table series. Laura Mulvey's article "Visual and Other Pleasures" came out, and everybody and their mama was using it, talking about the politics of the gaze, and I kept thinking of the gaps in her text, the way in which she had considered black female subjects

bh: That's exactly what I was thinking, though you and I didn't know each other at the time. Her piece was the catalyst for me to write my piece on black female spectators, articulating theoretically exactly what you were doing in the Kitchen Table series.

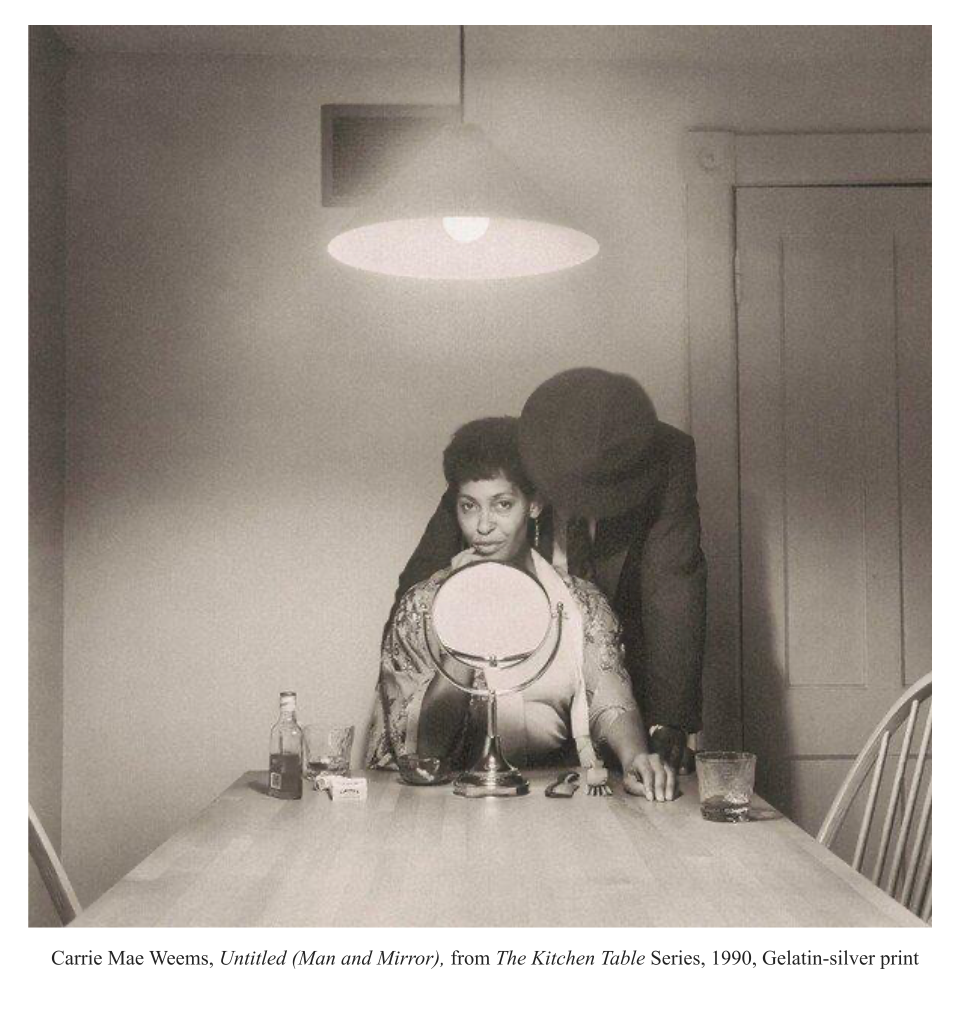

CMW: All the pieces in the Kitchen Table series highlight "the gaze," particularly the piece where the woman is sitting with a man leaning against her, his head buried in her neck, a mirror placed directly in front of her, but she looks beyond that to the subject (hooks 84).

The work Weems describes here is her photograph Untitled (Man and Mirror) from her 1990 Kitchen Table series. The series consists of numerous vignettes featuring Weems along with other subjects that all take place around the artist's dining room table. Several photographs in this series include mirrors as either active or passive objects in each vignette (Weems).

This use of mirrors is a recurring theme in Weems’s oeuvre. Arguably, this repeated motif is correlated to Weems’s awareness of the lack of female Black subjectivity. There is no better place for attempting to understand oneself than in the mirror. By looking in the mirror, people can simultaneously act both as the spectator and the subject with complete control, often within a highly private setting. Compare this to Laura Mulvey’s argument about scopophilia and narcissistic identification. Mulvey argues that filmgoers gain pleasure both through the act of looking and through identifying themselves with the subjects on screen. She goes on to say, “The extreme contrast between the darkness in the auditorium and the brilliance of the shifting patterns of light and shade on the screen helps to promote the illusion of voyeuristic separation.” (714). By allowing oneself to watch and identify with the subjects within the safety of a dark theater, viewers begin to understand the work around them through the lens constructed by Hollywood. When there is no one on screen, viewers are left to construct identities through other means. This is where self-spectatorship in the mirror becomes so important. Much like Claude Cahun in their 1928 Self Portrait, Weems uses the mirror as a way to highlight how self-spectatorship can be a substitute for narcissistic identification when one is not represented on screen or within art history.

This also connects to hooks's idea of the Oppositional Gaze. Because underrepresented spectators have had to learn to watch and analyze media through an oppositional lens, the viewing experience is inherently unrelaxed. While those represented in the media indulge in self-definition within the safety of a dark movie theater, those whose identities are underrepresented look to the home and the privacy of mirrors as a location to build identity. By engaging with the pleasure of self-spectatorship and allowing oneself to build identity and develop new ways of looking through the mirror, those along the margins are able to use the mirror as a tool to redefine the self.

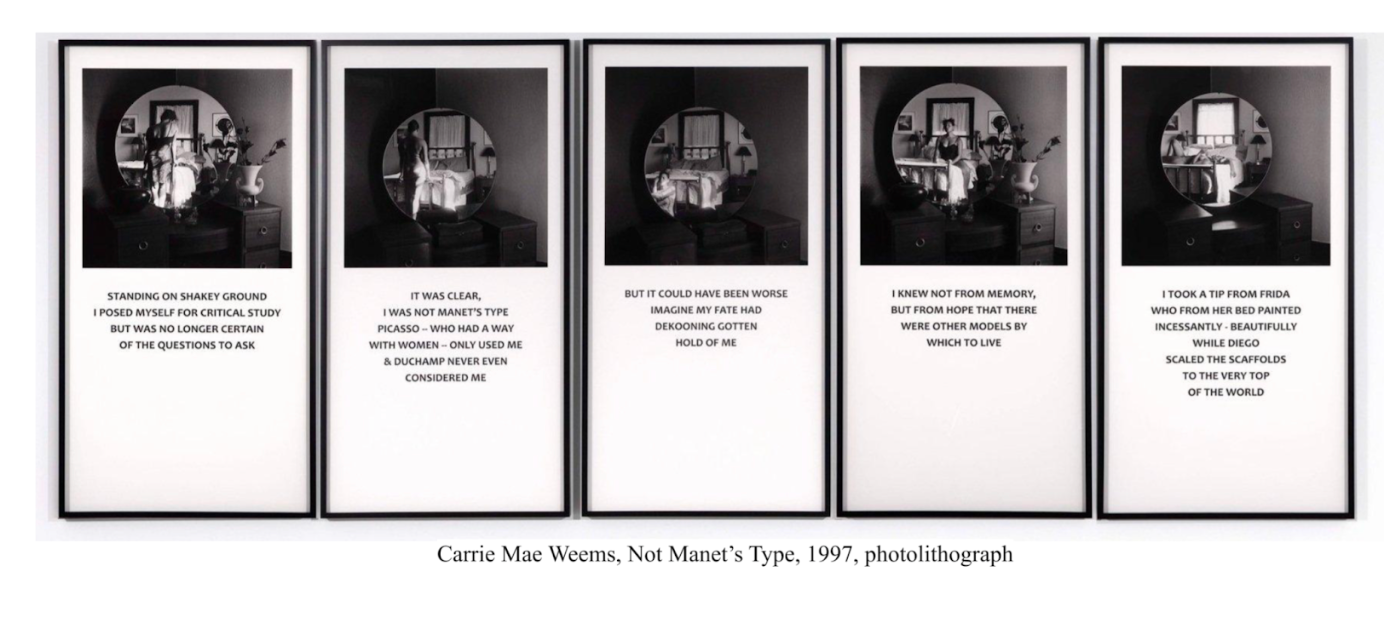

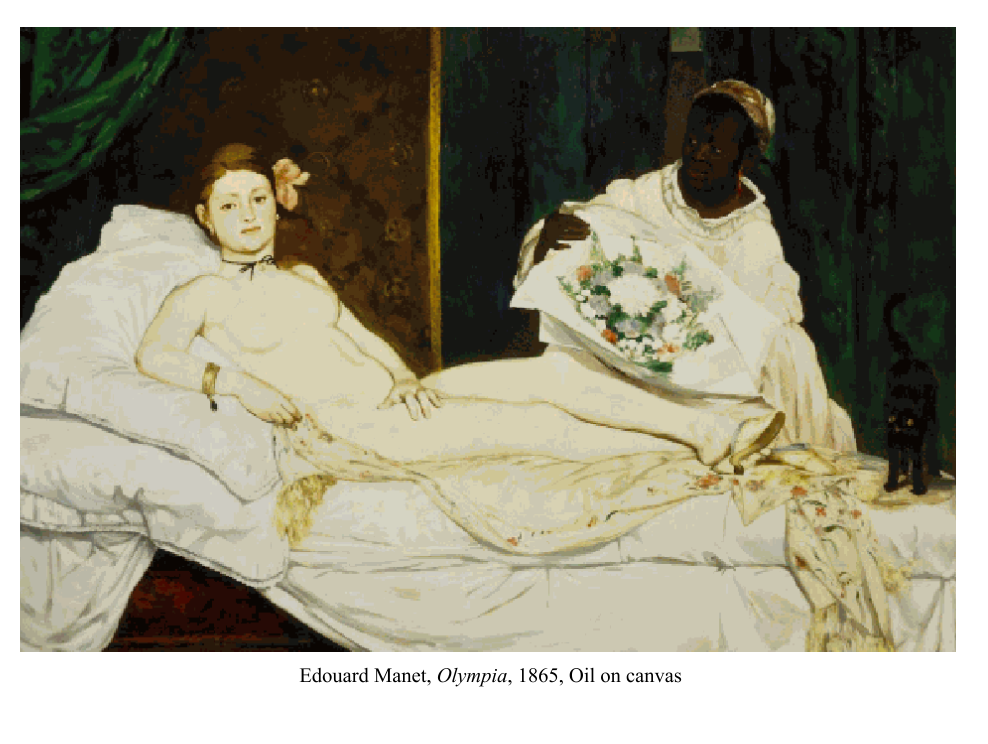

While Mulvey was one of the first scholars to write about the gaze as it pertains to film, these same basic desires lay within viewership and subjectivity of all kinds. Before film and photography, artists used different media to construct meaning and maintain social roles. Much like in photography and film, Black subjectivity was either absent or subjects were relegated and flattened into stereotypes. Weems acknowledges and challenges this lack of representation in her 1997 series Not Manet’s Type. This series consists of five images of Weems photographed in the reflection of her bedroom mirror with accompanying text. The text describes Weem’s acute awareness of the lack of representation of Black women in art history. The caption under the first image reads “Standing on shaky ground / I posed myself for critical study / but was no longer certain / of the questions to ask.” The text then goes on to describe male Modernists who either excluded Black women from their work or depicted them in a flattened way. The series takes its title from the text under the second image, which references Manet’s 1863 painting Olympia and the Black servant tending to the titular subject (Shane 503). The three artists whom she names, Manet, Picasso, and Duchamp, are not the only artists guilty of this, but rather, Weems uses these giants of Modernism to illustrate a larger issue of exclusion.

The language she uses is also extremely purposeful. In the text, she notably uses first-person pronouns. She writes, “I was not Manet’s type / Picasso - who had a way / with women - only used me / & Duchamp never even / considered me.” The use of first-person pronouns is successful in two ways here. The first is by using this language, Weems places herself and her experience in the center of the conversation. Secondly, the use of this language allows her to act as a proxy for the underrepresentation of Black female subjects within the art historical canon.

It is also important to note that each of the five photographs in this series has the same distinct composition. In each image, the camera frames an Art Deco vanity with a large circular mirror. The mirror reflects Weems in her bedroom in various stages of undress in each of the photographs. Much like in Cahun and Sherman’s work, the mirror acts as our primary means of understanding the subject. Because of this, we as viewers inherently understand that we are seeing a reflection of Weems, rather than the artist in the flesh. This immediately gives the photographs a sense of intimacy as well. We are seeing Weems as she would see herself move through her bedroom in the reflection of the mirror. This is similar to how we are only able to see Cindy Sherman’s face in the mirror’s reflection in Untitled Film Still #81. The presence of the door frame in Sherman’s work and the mirror framing Weems also brings to mind feelings of voyeurism and the hyper-awareness that we, as viewers, are looking at a constructed image.

This feeling of scopophilia and intimacy is then doubled down through the distinctly domestic setting of Not Manet’s Type. The subject is at home, undressed, and caught in the act of self-spectatorship, much like in Claude Cahun’s 1928 Self Portrait. While Cahun’s setting is ambiguous, it is undeniable and conceptually pertinent that Not Manet’s Type features the artist's bedroom. In each photograph, Weems leans, sits, or lies on her bed. This is no accident. The text under the fifth and final photograph reads “I took a tip from Frida / who from her bed painted / incessantly-beautifully / while Diego / scaled the scaffolds / to the very top / of the world.” By comparing herself to Frida Kahlo, who often painted from bed due to chronic pain, Weems emphasizes the bed as a place for self-representation. This is especially notable because this is the only frame in which Weems can be seen at rest, lying nude in her bed.

Both Sherman and Weems use multiplicity and series to explore large themes of how perspectives of self are influenced by the art historical canon and mainstream media. Weems often does this through a series of photographs making up one piece, like Not Manet’s Type, while Sherman uses multiplicity on a larger scale, and works are shown separately. Neither of these uses of multiplicity is more or less effective, rather, they are used to communicate different things. In Not Manet’s Type, Weems uses multiple photographs to communicate a narrative. The photographs and text ask viewers to recognize the lack of representation and propose new ways of looking at and creating work. Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, on the other hand, have no narrative. By creating these vignettes, Sherman highlights the lack of dimensionality of female subjects and the constructed nature of subjectivity. Both artists arguably use multiplicity on opposite ends of the spectrum to point to the complexities of gendered representation. Weems uses the multiple to depict narratives around Black female subjects, while Sherman uses the multiple to point to the lack of dimensionality of (mostly white) female subjects in mainstream media and film.

While Claude Cahun, Cindy Sherman, and Carrie Mae Weems all have distinct visual styles and belong to different movements, their use of the mirror within photographic self-portraits allowed them to explore the complexities of self-spectatorship and identity. Throughout their work, all three question what it means to photograph oneself while centering their experience as members of marginalized groups. In Claude Cahun’s 1928 Self-Portrait, Cindy Sherman’s 1979 Untitled Film Still #81, and Carrie Mae Weems’s 1997 Not Manet’s Type, these artists explore the complexities of representation when questions of gender, gender-nonconformity, and race arise. They all employ mirrors and frames to explore how self-spectatorship changes when the private is made public. Cahun, Sherman, and Weems simultaneously use self-spectatorship and an open acknowledgement of the shortcomings of traditional portraiture to create work that establishes a new visual language to question what it means to create an image of oneself.

Works Cited

Barber, Fionna. "Art of the Avant Gardes." Surrealism, pp. 427–448.

Doane, Mary Ann. “Film and the Masquerade: Theorizing the Female Spectator.” Screen, vol. 23, no. 3–4, 1982, pp. 74–88.

“Frederick Douglass and the Power of Photography.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/frederick-douglass-and-the-power-of-photography.htm.

Giannachi, Gabriella. Technologies of the Self-Portrait: Identity, Presence and the Construction of the Subject(s) in Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Art. Routledge, 2022.

hooks, bell. Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. 1995, pp. 74–94, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics - bell hooks - Monoskop.

hooks, bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” Black Looks: Race and Representation, South End Press, 1992, pp. 115–131.

Jones, Emmanuel. "Mirror Mirror." Medium, https://medium.com/@edj3/reflecting-on-carrie-mae-weems-mirror-mirror-8191b4f7c3

Kline, Katy. "In or Out of the Picture." Mirror Images: Women, Surrealism, and Self-Representation, MIT Press, 1998, pp. 66–81.

Krauss, Rosalind E. Bachelors. The MIT Press, 1999.

Man Ray.Le Violon d'Ingres, Getty Museum, https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/104E4A.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 6-18

Potthast, Louisa. "You Can’t Keep a Good Woman Down: The Representation of Black Womanhood in the Photography of Carrie Mae Weems." University of Cologne, 2021, https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/53167/1/Louisa%20Potthast%20thesis.pdf.

Shane, Robert R. “‘I Longed to Cherish Mirrored Reflections’: Mirroring and Black Female

Subjectivity in Carrie Mae Weems’s Art against Shame.” Hypatia, vol. 33, no. 3, 2018, pp. 500–520. Web.

Weems, Carrie Mae. Kitchen Table Series. 1990, https://www.carriemaeweems.net/kitchentable.

Eat Your Heart Out

2023

Eat Your Heart Out is a limited-edition zine I made in the fall of 2023. This publication has come together due to the hard work of countless students, faculty, staff, and community members at Northeastern University. Over several months, I edited, and designed this publication as a part of my co-op at Gallery360 and the Center for the Arts. Eat Your Heart Out opens with an essay about food and contemporary art that I wrote as a kind of curatorial statement. The zine also includes thirteen student submissions that can start to give us some insights into thinking about food as art. Some of the student work includes poetry, essays, stories, recipes, and more. Each work is a wonderful example of the way food’s specificity as well as its transcendence. Beyond the body, beyond materiality, there is something innately creative and human about cooking, sharing, and eating food. At its root, Eat Your Heart Out is an intersection of my studio and curatorial practice. A PDF version of Eat Your Heart Out can be found here. Below is the introductory essay.

A few summers ago, I spent an especially hot day in the safety of the air-conditioned Portland Art Museum. While I have spent countless afternoons in the museum throughout the years, I can’t help but find my attention captured by a new corner of the museum each visit. On this particularly humid July afternoon, I found myself wandering around the museum’s American gallery comparing two still-life paintings, both of bowls of fruit (a little cliche, I know). Although I can’t remember the name of either artist, I remember thinking of how different their styles felt. The one to my left was sharp with each individual grape and cherry shining. The other painting had a softer touch allowing each piece of fruit to disappear into another.

On my walk home, I stumbled across a patch of sidewalk littered with cherries and grapes. I remember thinking about how funny it was to come across this after spending my afternoon in the still-life gallery. I then thought of the misfortune of whoever had taken the time to pack the lunch that now covered the pavement.

In both the still lifes and on the sidewalk, the intention and care in the preparation of the fruit was clear. Seeing the spilled fruit also made me think of the unspoken sadness that lurks behind many still-life paintings. While they may feel dated today, paintings of fruit or bountiful harvests have long been associated with wealth and prosperity. When I look at these paintings’ grandiose displays of power, I always find myself thinking about disparities in resources. My sadness is deepened when I think about how much of the fruit in these paintings would have gone uneaten. I remember thinking about how the fruit on the sidewalk would inevitably have the same fate.

It may just be a side effect of my art history education, but I couldn’t help but think about the parallels between the cherries on the sidewalk and in the museum. While it might seem odd, I remember thinking that the spilled cherries acted as a perfect (if accidental) subversion of the fruit in the museum. The portioned and prepared fruit had clearly been treated with intention and care yet would go untouched. This prompted me to explore themes surrounding food in art both within my painting practice and my academic studies.

Food is something that has always been depicted in art. It is something that everyone can see, understand, and place within their own life. Nearly everyone has some kind of memory based on cooking and eating regardless of time or place. In addition to food’s cultural and personal significance, it also literally nourishes the body. No matter how much I think and read about food, I consistently find myself coming back to the idea of care and community.

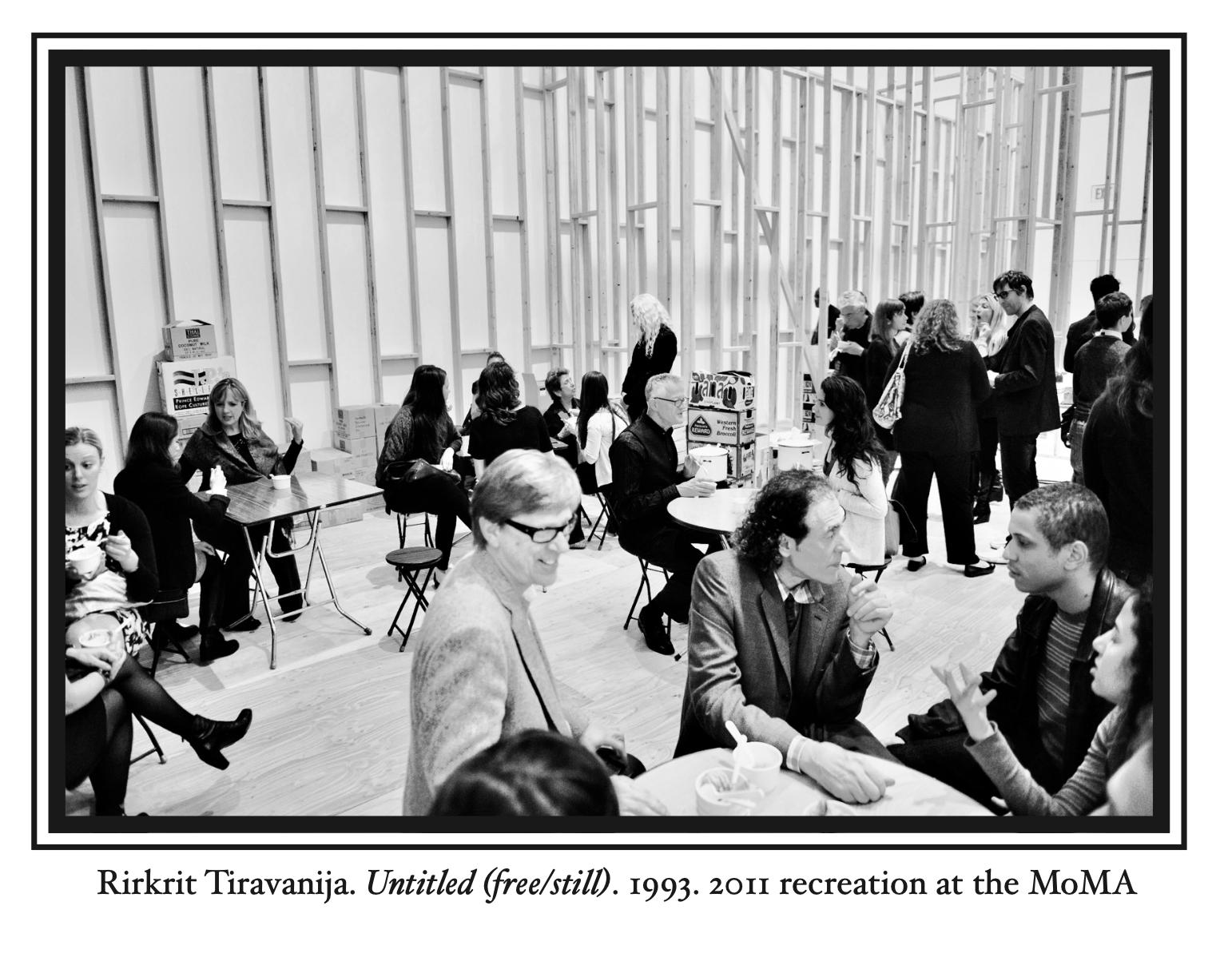

It is not only the food itself that is significant but the act of eating as well. For centuries, artists have explored the dinner table as a location for community bonding. Whether it’s Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper or Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, the table is a tangible and recognizable place for conversation and gathering that has long been represented in art. But what happens when you break this idea down to its most basic principles? All you need is something to eat and at least two people. Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija explores this idea through his deceptively simple 1992 piece Untitled (free/still).

Living somewhere between performance and installation, Tiravanija allows the audience to participate in the ritual of gathering to eat. The piece consists of rice, curry, and a seating area. Visitors are encouraged to sit, eat, and talk with each other to activate the piece. Tiravanija created a community-based piece that turns an everyday act into a work of art. By participating in this piece, people are given an experience as well as a reminder of the importance of sharing food. Untitled (free/still) gives people an opportunity to turn an everyday activity into an act of self and community care.

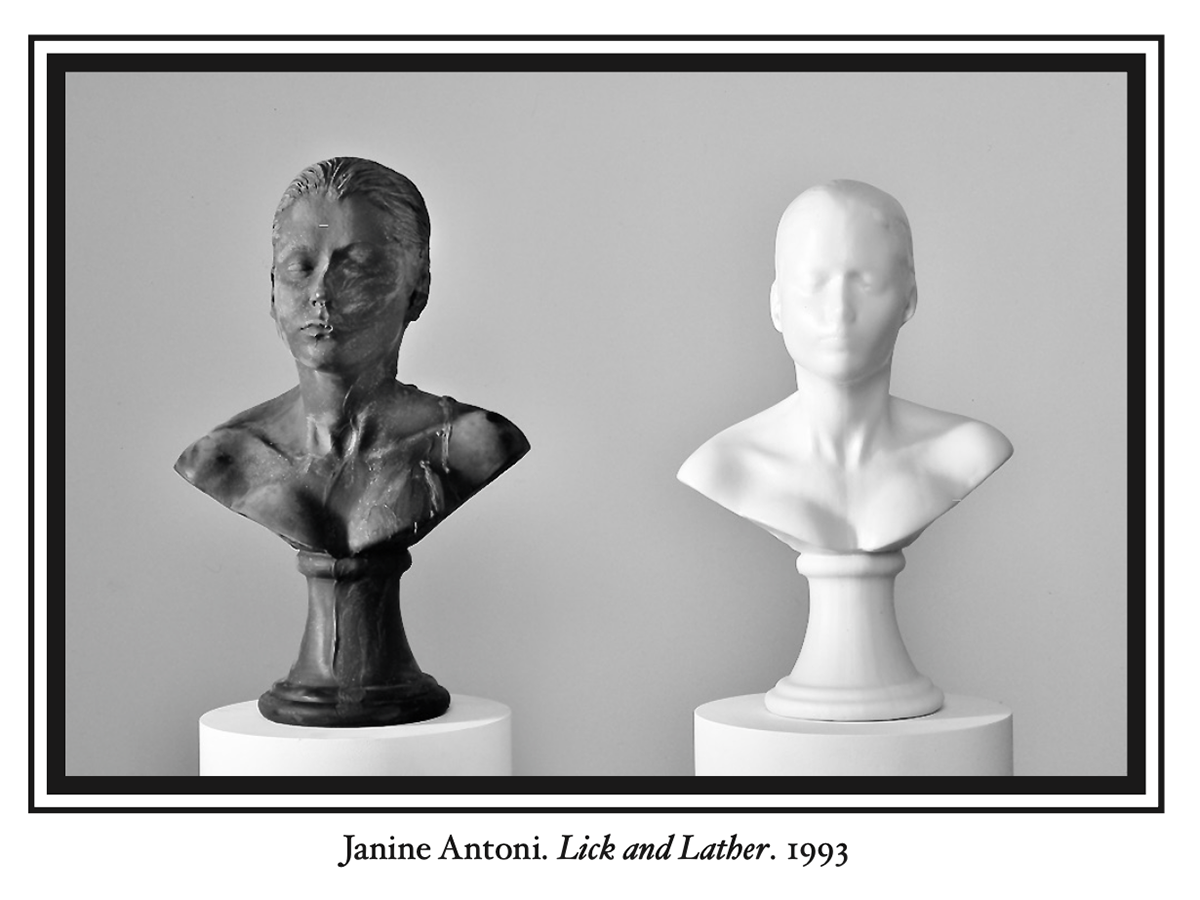

Rirkrit Tiravanija is far from the only artist to explore this intersection of food and care. Beyond Tiravanija’s exploration of eating as a community-based practice, other artists have used food to investigate themes of self-care and the body. Janine Antoni is an artist who uses sculpture and performance to investigate her body’s relationship to food. No piece does this as directly as her 1993 piece Lick and Lather. In this piece, Antoni cast fourteen busts of herself, seven in chocolate and seven in soap. Antoni then performs with the busts by licking the chocolate and bathing herself with the soap. Both of these acts are very different from one another, and yet they both leave the busts in “worse” condition. As Antoni performs with these pieces, the detail of her facial features is gradually erased until the busts are no longer recognizable.

The materiality of the busts is fundamental to Lick and Lather’s conceptual backing. Not only do the chocolate and soap play an important role in the performance, but they also provide an important aesthetic quality. Historically, busts are cast in bronze or carved in marble and are associated with Classical or Neoclassical movements. By creating chocolate and soap busts of herself, Antoni places herself, both as a maker and as a subject, within an instantly recognizable visual language. Even though these sculptures reference seemingly timeless busts, both the soap and chocolate are materials that age and degrade rapidly. While this might seem like a side effect, the deterioration is integral to the piece. This intentional decay acts as a reminder both of the temporality of the piece and of the body.

When Antoni licks and bathes using the busts, she is literally using her body to perform these acts of care. With each performance, Antoni’s features become increasingly obscured until the busts are unrecognizable. Despite the erasure of the artist’s identity with each performance, Antoni describes this performance as one of gentleness and care. The finite nature of this piece and Antoni’s comfort with the temporality of the body acts as a reminder of the importance of the gentleness and care we all must give ourselves.

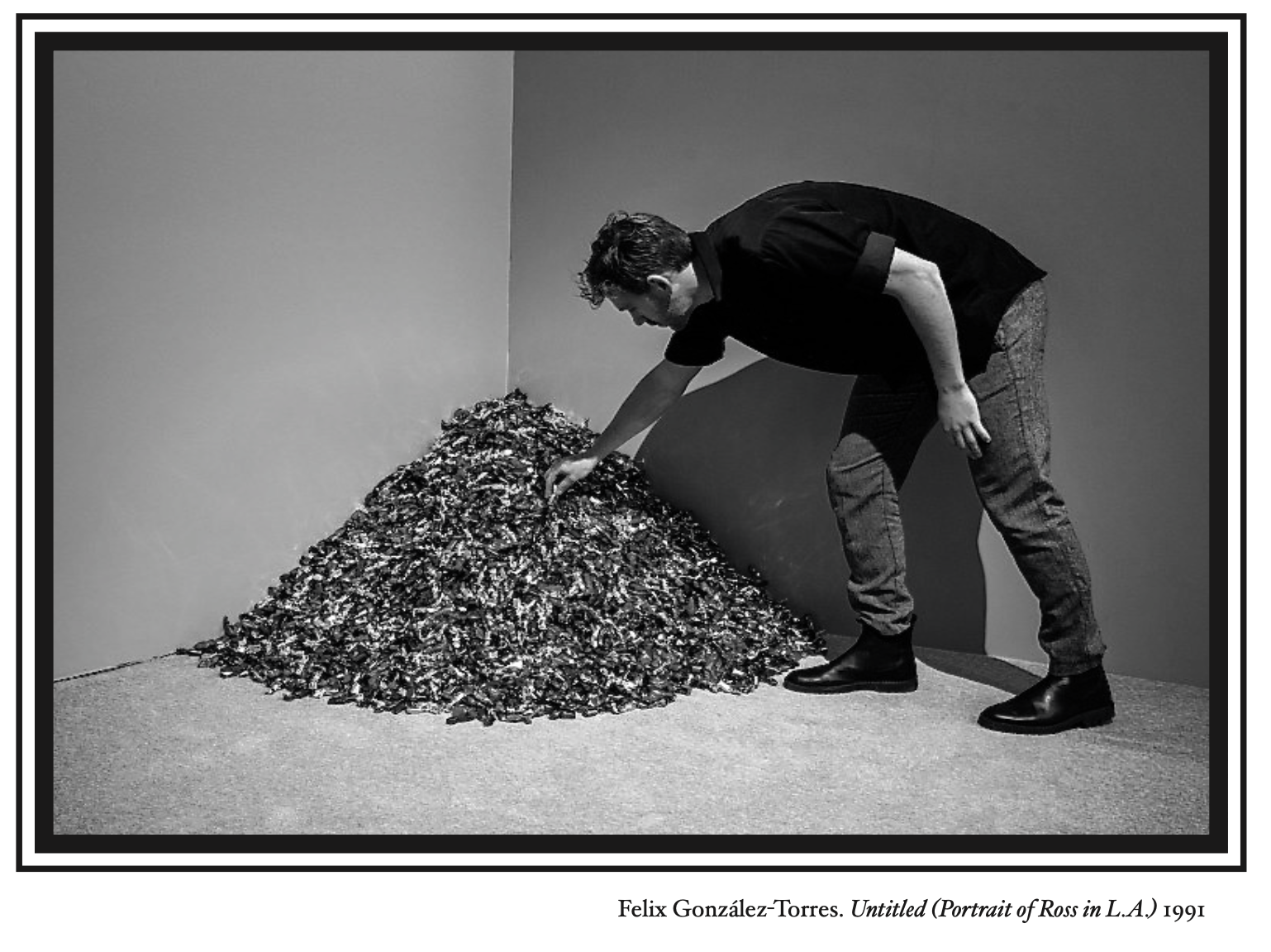

Where Antoni’s reference to the body is quite literal, other artists have used food to represent the body in more abstract ways. One of these artists is the late Cuban-American artist Félix González-Torres whose work consists of conceptually-driven minimalist works surrounding themes of queerness, intimacy, and the HIV-Aids epidemic Throughout his practice, González-Torres uses common household objects to create thought-provoking work that

often deals with highly personal themes. One technique he used throughout his practice was multiplicity and audience participation. There is no better example of this than in his 1991 piece Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.). The piece consists of 175 pounds of multicolored candy in a pile on the floor. While many will have encountered these sweets, they feel foreign displayed in this context. Viewers are invited to take and eat the candy from the pile. The piece is regularly replenished but it rarely lives at 175 pounds and is constantly in flux. Because of the constant change in mass and shape, the piece feels alive.

The weight of the piece refers to the weight of Ross Laycock, González-Torres’s partner, who died from complications due to Aids in January of 1991, just months before the creation of this piece. Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)’s constantly dwindling weight parallels Laycock’s significant weight loss in the months before his passing. There are two primary functions of allowing people to eat Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.). The first is allowing for people to find joy in communal consumption much like in Tiravanija’s piece. This act of eating allows time for care and nourishment within a contemporary art space.

Through this act, González-Torres creates intimacy between viewers, himself, and Ross. Importantly, when viewers eat the candy, they allow the piece to become a part of their body. This leads to the second and arguably more important function of this piece. Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) invited viewers to touch a portrait of someone who was HIV-positive. While there is still much stigma today, the fear and demonization of people with HIV-Aids in the 1980s and 90s was especially rampant. There was a widespread and false belief that touching someone who is HIV-positive would spread the virus. This caused countless people to die unnecessarily because they could not get basic medical care.

In Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), González-Torres asks people to engage in this caring act of sharing food using this abstracted representation of Ross Laycock. This piece so perfectly strikes a balance of care and heartbreak. While the act of sharing candy is joyful, each piece chips away at the 175-pound pile, representing Laycock’s decline. By eating the candy, people are not only touching this portrait of Ross, but they are allowing this abstract representation of his body to nourish them —both literally and figuratively.

As much as I’d like to make dinner, share candy, or pack cherries for everyone reading this, I, much like Rirkrit Tiravanija, Janine Antoni, Félix González-Torres, understand the difficulties of care, community, food, and ephemerality. Instead of trying to fight the temporality of food, I instead offer you this publication! Over the last few months, I have spent a lot of time talking and thinking about food both within the context of my own life and on a communal level. Of course, I can only speak from my experiences. I found some of the most fruitful conversations I had about food were with my peers. It is because of this, that I reached out to the Northeastern community looking for stories, recipes, poems, etc that could give a fuller picture of how people relate to the food they eat.

The following includes thirteen student submissions that can start to give us some insights into thinking about food as art. Like the work of González-Torres, all thirteen of the following are deeply personal. Students explored themes of food, art, and memory through poetry, essays, stories, recipes, and more. Each work is a wonderful example of the way food’s specificity as well as its transcendence. Beyond the body, beyond materiality, there is something innately creative and human about cooking, sharing, and eating food. I hope that Eat Your Heart Out can act as a form of emotional and intellectual nourishment to everyone who reads it. (You could try to eat it too but I don’t think it would taste very good!)

Works Cited

“Janine Antoni in ‘Loss & Desire,’” Art21, accessed December 12, 2023, https://art21.org/watch/art-in-the-twenty-first-century/s2/janine-antoni-in-loss-desire-segment/.

“Lick and Lather,” National Gallery of Art, accessed December 12, 2023, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.206257.html.

Stokes, Rebecca “Rirkrit Tiravanija: Cooking Up an Art Experience,” [INSIDE/OUT], Museum of Modern Art, February 3, 2012.. https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2012/02/03/rirkrit-tiravanija-cooking-up-an-art-experience/.

“Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.),” the Art Institute of Chicago, accessed December 122023 https://www.artic.edu/artworks/152961/untitled-portrait-of-ross-in-l-a.

Woodley, Bayley, “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.),” Queer Art History, December 2, 2022, https://www.queerarthistory.com/love-between-men/untitled-portrait-of-ross-in-l-a/.

“You’ve Never Seen Sculptures Like Lick and Lather Before,” Smithsonian Institution, accessed December 12, 2023, https://www.si.edu/object/youaposve-never-seen- sculptures-lick-and-lather:yt_7nD1y0iTz5U